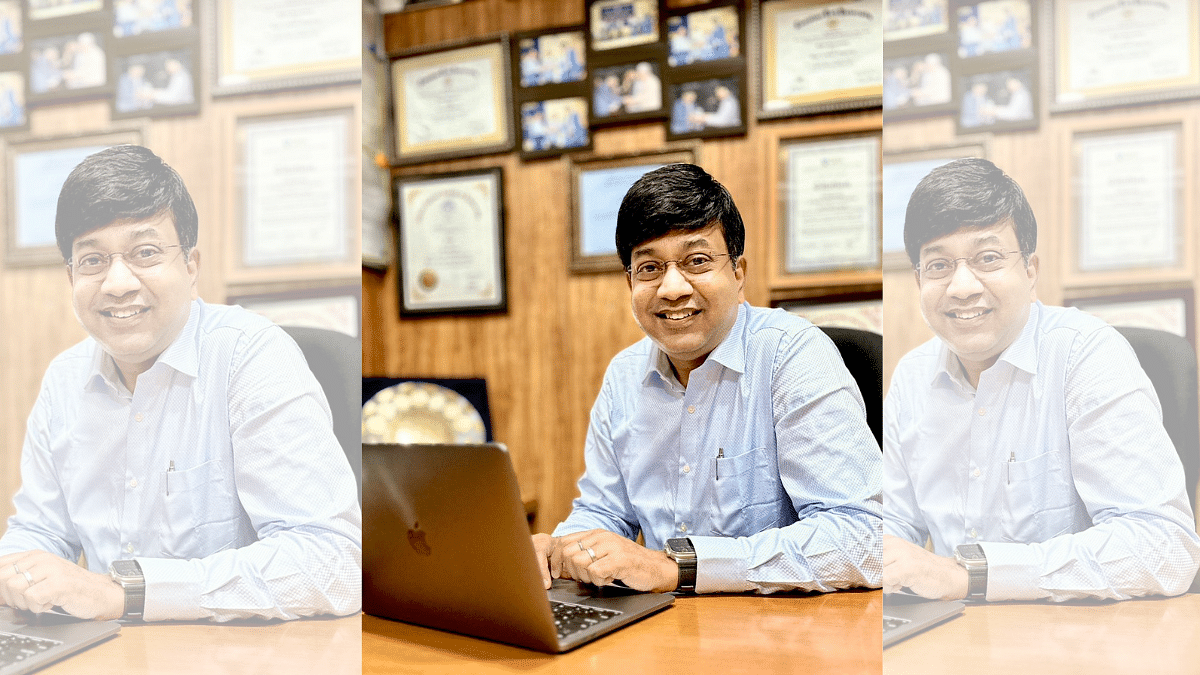

New Delhi: Rohit Srivastava, a professor at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, who has filed more than 250 patents and been granted over 80, is one of the Vigyan Shri awardees honoured by the Indian government for distinguished contribution in the field of Science and Technology.

His seminal work in biomedical engineering, especially in the area of affordable healthcare devices in the Indian market, led him to be recognised under the “Technology and Innovation” category of the Rashtriya Vigyan Puraskar 2024, which fetes outstanding researchers in the fields of science, technology and innovation.

Srivastava and his team have the reputation of looking beyond papers and conferences in the field of biomedical sciences. Over the years, they have developed handy and affordable devices, like a mobile phone-based diagnostic device and a convenient blood sugar tester.

In an interview to ThePrint, Srivastava said that digital health research has gained importance, especially since the Covid pandemic.

Also read: Science ministry proposes new Rashtriya Vigyan Puraskar as India’s highest science & tech honour

Here are the edited excerpts:

Could you talk about your area of expertise, specifically your work in affordable healthcare?

I’ve been at IIT-Bombay for the past 20 years. When I joined, biomedical engineering was at its nascent stage. Biomedical engineering scientists were very few in the country since it was an interdisciplinary field and not many understood its impact. Over the years, we’ve worked with not just engineers but medical professionals too, to build ideas that go from the lab to the market. That’s the biggest impact of this field.

Years ago, an MTech student joined my lab and he wanted to work on real-life problems. I said we shouldn’t just concentrate on papers, publications, and conferences, but also create a medical device that will help the country – by bringing affordable technology to the market which would also help us be self-reliant.

The first thing we noticed in the Indian market was the need to miniaturise tests being done at pathology labs and make a single point-of-care device. In 2010, we were able to create a mobile phone-based diagnostic device called “uChek” which is as efficient as a Clinitek machine found in pathology labs for urine analysis, but at one-fifth the cost. We then came up with an indigenous glucometer too, called Suchek, and released this device in the New Delhi market in 2013.

A diabetic who has to check his sugar levels 4 to 5 times a day cannot afford a Rs 18 strip even today, and our device made these strips available at less than Rs 5. Our strips made a huge impact on affordability.

With these two products and many more that came out of our lab, we established ourselves as one of the premier labs in the country doing “translational research”. This term was coined very recently because the government wanted to focus on technologies that could go from research to the market. Today, I’m proud to say that what we started in our lab has taken wings and gone to several other labs in the country.

How did you find your niche in the field of science, technology and innovation? What was your academic journey?

I completed my Bachelors in electrical engineering from Nagpur. I could have got a job in a leading software consultancy firm, but it meant I had to leave my field. This is where I needed to decide what my passion was — it was to make use of my engineering degree for the betterment of the country. I chose to pursue higher education abroad to check the international flavour of how things were done.

I came back after finishing my PhD in biomedical engineering at Louisiana Tech University, US, and joined IIT-Bombay with no post-doc experience. Starting my own lab was my post-doc. I knew what I wanted to do would pave the way not just for me but for many future students. I trained my students to be independent in their approach and use the knowledge of their respective backgrounds in the medical field — be it in engineering, pharmaceuticals or biotechnology.

One has to think about what one wants to do in life before taking the leap into academics or industry.

How have you seen the growth of science and technology, especially in relation to healthcare, in public opinion and the field itself, especially post Covid?

When I joined engineering, the focus was either on electrical engineering or computer science. There were very few students doing anything else. Today, after this country fought Covid and could create its own vaccines and diagnostic devices, people became aware of the huge field of medical engineering. Many students, studying computer science, chemical, mechanical or electrical engineering or even physics, are looking to do interdisciplinary research with medical professionals.

Digital health research has become an important area, especially after COVID, as we can now remotely look at scans, and even diagnose people from afar. Many in the country live in far-off places with no access to doctors and large hospitals, so this is huge for them. My personal view is that COVID didn’t just bring about a change in the world, but also in people’s mindset to look at healthcare problems more widely.

This is the first set of Vigyan awards by the Indian government. There were some divisive opinions when they were first announced. But how does it feel to be a recipient?

Let me take a step back and elaborate on how we’ve now changed the process of giving awards. Initially, every organisation was giving awards. I’ve myself got it from all of them — science ministries, and private organisations. The biggest one before this was the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Prize, of which I was the first engineer to get it in the medical science category. It was an eye-opener that the country was recognising medical advances by engineers in the field.

There was a phase when the country decided to bring these awards under one umbrella. I personally feel it is the right decision because it motivates us to work for the country, not for an award. We’re working to translate our research into market acceptability and to benefit the common people.

Finally, it is heartening to see the country recognising your work with an award. There are many award categories in the country, but this is the first time that a category has been created for technology and innovation, and the first time the country has given it to someone like me because of the impact we’ve created.

We’ve filed more than 250 patents, which is the largest number for any individual in the entire southern hemisphere. And many of these have been translated into actual products that have benefited people. That is what my country has recognised. I am forever grateful to the government for it.

(Edited by Tikli Basu)

Also read: Scientists from IITs, TIFR, IITM-Pune in list of first Rashtriya Vigyan Puruskar awardees