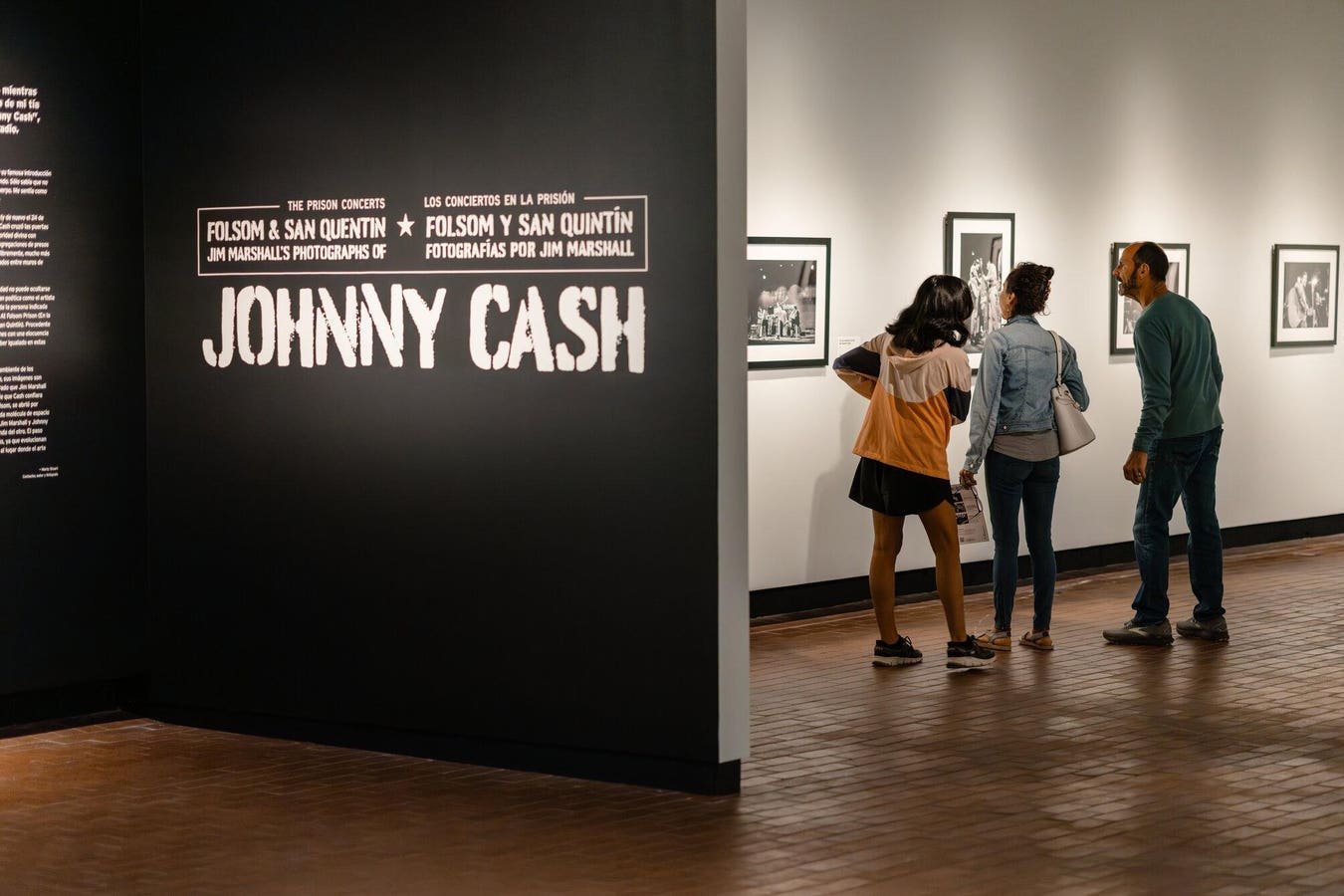

“The Prison Concerts: Folsom And San Quentin (Jim Marshall’s Photographs of Johnny Cash),” installation view at the Momentary in Bentonville, AR.

Jared Sorrells for the Momentary

Johnny Cash was a protest singer. The genre was country, but the message was protest. America’s mistreatment of Native Americans, veterans, working people, poor people.

Most famously, America’s mistreatment of incarcerated people.

Songs including “Folsom Prison Blues,” “I Got Stripes,” “Jacob Green,” “Man in Black,” “The Wall,” “Starkville City Jail,” and “San Quentin” all showed empathy for inmates in a country that has almost none. Cash spent a couple nights in jail, but never did prison time. As an artist, as an empath, he didn’t need to to understand how barbaric caging people was.

“San Quentin, what good do you think you do?

Do you think I’ll be different when you’re through?

You bent my heart and mind and you warp my soul

And your stone walls turn my blood a little cold.”

“Jacob Green” offers an even fiercer indictment of the prison system. A young man busted for the simple offense of possession is humiliated and abused by his guards resulting suicide.

America’s worst-in-the-free-world prison system would become dramatically worse following the height of Cash’s prison advocacy and chart popularity in the 1960s and 1970s. The nation’s so-called “war on drugs” and “get tough on crime” hysteria fostered during the Nixon Administration and accelerated under Ronald Reagan did nothing to abate drug use or reduce crime, but prison populations exploded as petty criminals and drug users were locked away.

Today, America imprisons more people than any other democracy on earth by a wide margin.

A disproportionate percentage of these inmates were and are Black and poor. America’s system of “criminal justice” from policing to prosecution to punishment has always been rigged against poor people and minorities.

Cash saw this 50-plus years ago. He was awake to the injustice. Woke.

The singer testified before Congress and met with Nixon in 1972 to discuss prison reform.

Still a patriot through and through, despite it all, Cash exposed the stupidity of the old right-wing saw, “love it or leave it.” Cash loved it and wanted to use his songs to make it better. He knew America wasn’t perfect. That obvious conclusion didn’t mean he didn’t love it.

Johnny Cash At Folsom And San Quentin

“The Prison Concerts: Folsom And San Quentin (Jim Marshall’s Photographs of Johnny Cash),” installation view at the Momentary in Bentonville, AR.

Jared Sorrells photography for the Momentary.

Cash first played at Folsom in 1966. He wrote “Folsom Prison Blues” way back in 1953, his first big hit. The song came to him after watching “Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison” (1951) while serving in the Air Force in West Germany.

In 1968, Johnny Cash was spiraling personally and professionally. An idea he pitched to his record label many years prior of performing live at the notorious state prison in Folsom, CA was finally approved after a leadership shakeup at Columbia Records. The company’s hopes were not high. Conventional wisdom held that country music’s ultra-conservative, Bible-thumping, “law and order,” fan base wouldn’t be interested in hearing Cash sing to and dignify criminals.

On January 13, 1968, Johnny Cash showed up at Folsom for the show along with June Carter–the duo would marry two weeks later–his band, the Tennessee Three, and opening acts and background singers the Statler Brothers and Carl Perkins.

Cash turned in a fully engaged performance for the ages. When the album was released later that spring, the public went wild. Number one album. Number one single. Grammy award.

Cash actually played two separate shows that day, assuring the album would have enough quality recorded material to choose from. The first take was nearly perfect.

Cash was back, off the strength of a live album recorded in a maximum-security prison to an audience most country music fans would recommend be executed, not entertained. Such is the power of music.

The following year, he gave a similarly lauded in-person, in prison performance at San Quentin. He performed for inmates multiple times.

Jim Marshall

Johnny, June, and the band were joined by music photographer Jim Marshall at the Folsom and San Quentin concerts. Requested personally by Cash, Marshall was the only official photographer present at the concerts and granted unlimited access.

Twenty-five photographs documenting the two concerts, including candid and performance images helping solidify Cash as an outlaw king can be seen through October 12, 2025, at The Momentary, an art exhibition and live music space, in Bentonville, AR, Cash’s home state.

“The Prison Concerts: Folsom and San Quentin (Jim Marshall’s Photographs of Johnny Cash)” showcases the powerful snapshots of a legendary musician by a legendary photographer. The presentation is free to the public.

“The godfather of music photography,” Marshall (1936–2010) maintained a 50-year career that resulted in more than 500 album covers, an abundance of magazine covers, and some of the most celebrated images in blues, jazz, country, and rock and roll, including those from Cash’s Folsom and San Quentin prison concerts.

Tall. Lean. Pompadour.

Cash is dressed in his trademark black although “the Man in Black” moniker wouldn’t come formally until the early 70s, in part resulting from his stark outfits at the prison concerts.

His 1971 hit “Man in Black” explains “why you never see bright colors on my back.”

It was a wardrobe of protest from a protest singer.

“I wear the black for the poor and the beaten down

Living in the hopeless, hungry side of town

I wear it for the prisoner who has long paid for his crime

But is there because he’s a victim of the time.”

Cash was in his late 30s when he gave the performances. He looks at least 10 years older. Growing up poor and hard living always made Cash appear much older than he actually was.

Marshall’s Folsom photos show the deep lines on the singer’s face. The weight of the world seemingly on his shoulders. Cash is serious, resolute, commanding. He’s going to work.

Cash isn’t nervous, certainly not afraid, but there’s a hint of self-doubt in his countenance and posture. “This might not work,” he seems to think to himself.

The prison’s stone façade looks positively medieval.

A photo of Cash lighting a cigarette with a more hopeful looking June Carter in the foreground looks so much like Joaquin Phoenix, the actor who played him in the biopic, it forces a doubletake.

Tragically, Folsom State Prison continues housing inmates today despite opening in 1880. Only San Quentin is older in California.