As evening settled on January 7, Pasadena, California, resident Colin Weatherby wasn’t on the watch for wildfires. He was worried about his windows.

“My building was built in 1951, and we have terrible windows,” the documentary film producer said from his apartment with a sweeping view of the nearby hills. Earlier that week, the National Weather Service had issued a warning for “potentially life threatening” high winds and Weatherby was concerned about how his aging windows would hold up.

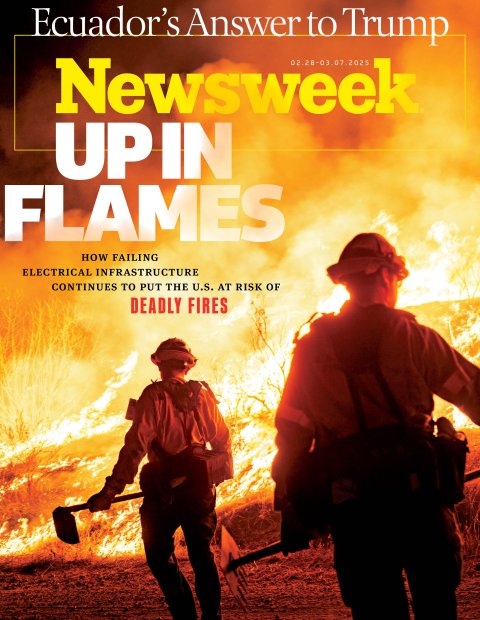

Eric Thayer/Getty

“The wind was tremendous,” he said.

As he watched the glass rattle, Weatherby saw some neighborhoods in the valley go dark as electric transformers blew out.

“I saw one of the transformers pop on the hillside in Eaton Canyon,” he said. Then, just below an electric transmission line tower on the hillside, he saw something more ominous. “Within a minute, I saw a flame start.”

What Weatherby saw that night could have been the origin of the Eaton fire that would burn for weeks, killing at least 17 people and destroying more than 9,000 homes, businesses and other structures. Eaton Canyon is also home to Weatherby’s parents. He called them immediately.

“I said, ‘A fire has just started right near your house,'” Weatherby said. “And in the course of the phone call, the fire just erupted.”

Hans Gutknecht/MediaNews Group/Los Angeles Daily News/Getty

Spate of Lethal Fires Caused by Equipment Failures

A raft of lawsuits filed on behalf of people who lost homes in the fire claim that eyewitness accounts like Weatherby’s, security camera footage and power-line sensing equipment all provide evidence that the electrical system belonging to the area utility company, Southern California Edison, SCE, is to blame.

The utility provider’s parent company, Edison International, has said it is too early to know the cause. In a video statement released on February 6, Edison International President and CEO Pedro Pizarro said the company is conducting a thorough investigation.

“While we do not yet know what caused the Eaton wildfire, SCE is exploring every possibility in its investigation, including the possibility that SCE’s equipment was involved,” Pizarro said.

OSH EDELSON/AFP/Getty

In a report filed with state regulators, the company agreed with the Los Angeles Fire Department that its electrical equipment was likely linked to another nearby fire in January, the Hurst fire, which burned about 800 acres near San Fernando.

Electrical arcs and sparks from faulty or damaged power lines and other electrical equipment can easily start a wildfire. And while it is not the main source of ignition for fires—lightning is a far more common cause—electrical equipment ignition is a growing problem in California and other fire-prone parts of the country.

California law requires the state’s three major electric utility companies to report any fire linked to electrical equipment that burns more than a square meter of ground. In 2023, state data shows, electrical equipment sparked 479 fires.

ETIENNE LAURENT/AFP/Getty

Most of those were small blazes that did little or no damage. But some of the state’s—and the nation’s—most damaging and deadly fires in the past decade were caused by power equipment.

The 2018 Camp fire in northern California that destroyed the town of Paradise and killed 85 people was sparked by an aging and poorly maintained power line owned by Pacific Gas & Electric. The liability pushed the company into bankruptcy. Multiple investigations of the 2023 fire that destroyed much of the town of Lahaina, Hawaii, killing 102 people, found that the blaze was caused by a downed power line. And last year utility company Xcel acknowledged that its equipment caused the Smokehouse Creek fire in Texas, the largest fire in the state’s history.

The fires are the result of a confluence of combustible trends. Development is pushing more housing into fire-prone wooded and grassland areas. Power demand is surging while the electrical infrastructure in many areas is aging. And behind all of this, scientists say, our warming climate makes fires more likely and more intense.

Despite tens of billions of dollars spent so far in California alone to reduce the risk of electric ignition, last month’s infernos suggest that much more needs to be done to make sure the electric grid does not contribute to more tragedy.

Justin Sullivan/Getty

Trying To Reduce Fire Risk

“It keeps me up at night, it does,” Doug Dorr said of the wildfire problem. Dorr is a technical executive with the Electric Power Research Institute, where he gets paid to think about the nightmare scenarios for electrical equipment fires and test ways to prevent them.

Tree limbs and other vegetation, animals and high winds are all potential threats. At a wildfire test facility in Lenox, Massachusetts, Dorr and his colleagues toss limbs and sticks across electric cables, measure the “wind slap” of power lines that get too close in heavy gusts and test cutting-edge detection equipment to catch electric faults.

The group recently finished a research program with the U.S. Department of Energy and about 100 wildfire advisers from utilities around the world that resulted in a catalog of more than 50 technologies that can help reduce fire risk. Those include conductor coverings, smoke detecting cameras and line sensors that can help predict equipment failures.

DAVID PASHAEE/Middle East Images/AFP/Getty

“None of them in a stand-alone mode can fix everything,” Dorr said. “But when you start to mix and match those you’ve got a much better chance of avoiding the ignition.”

Everything in the catalog is being used by at least one utility somewhere in the world, Dorr said. Strategic undergrounding of power lines makes them far less likely to fail. But it can be prohibitively expensive to bury cables in some places and simply not possible in others where rock is close to the surface, Dorr said. He’s excited about the potential for a hybrid on-ground system now undergoing tests at the Lenox facility.

“It’s on the ground and it’s in a protective enclosure, which means that it’s unlikely to get damaged and create any kind of problems,” he said.

The cost of line sensor devices is dropping, Dorr said, and artificial intelligence can help to more quickly put data from sensors to work to predict problems. In short, Dorr said, solutions abound.

ALI MATIN/Middle East Images/AFP/Getty

“It’s not a matter of innovation,” he said. “We have the ideas.”

The main challenge now is the costly and time- consuming work of putting those solutions in place across thousands of miles of electrical lines. In a July report to the California legislature, the state’s Public Utilities Commission added up the costs of wildfire mitigation work utility companies had done over the previous four years. The total: $16.4 billion. Another $10 billion went toward wildfire insurance and payments for catastrophic events.

“Wildfire mitigation costs have climbed since 2021 and are projected to continue their upward trend,” the report warned, and the PUC named a culprit: climate change-induced risks.

“Climate change is escalating, with stronger storms, hotter temperatures and conditions that increase the risk of catastrophic wildfire,” the report said.

Roger Kisby/Bloomberg/Getty

Warming Planet Heightens Risk of Fires

When extreme weather disasters such as floods, heat waves or wildfires strike, World Weather Attribution, an international network of climate scientists established in 2014, works to determine how much climate change might have contributed. Climate scientists have long known that a warming climate makes wildfires worse. In the wake of the L.A. fires, World Weather Attribution scientists from the U.S. and six other nations swiftly investigated the climate fingerprints on the fires.

They found with “high confidence” that “human-induced climate change, primarily driven by the burning of fossil fuels, increased the likelihood of the devastating L.A. fires.”

The scientists looked at the connections between warming, drought and the collection of conditions that together make up what’s known as the Fire Weather Index. They found that the high index in Los Angeles in January was about 35 percent more likely than it would be in a cooler climate without greenhouse gases. Further, they warned that the likelihood and intensity of fire conditions will continue to increase with more warming.

Mario Tama/Getty

While the fires raged in the hills around Los Angeles, scientists at UCLA published a study explaining how the extreme swings in precipitation caused by climate change created a phenomenon they called “hydroclimate whiplash” that added fuel for the fires.

Abnormally heavy rainfall in the atmospheric river events of 2023 triggered a burst of vegetation. Then 2024 brought a record-hot summer and extremely dry conditions leading up to the fires.

“This whiplash sequence in California has increased fire risk twofold,” UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain explained in a release accompanying the study. “First by greatly increasing the growth of flammable grass and brush in the months leading up to fire season, and then by drying it out to exceptionally high levels with the extreme dryness and warmth that followed.”

APU GOMES/AFP/Getty

As climate change makes fire conditions more likely, scientists have also found that the fires that humans spark tend to be worse than ones ignited by natural causes such as lightning.

In a study published in the journal Nature Communications in 2022, scientists from University of California Irvine found that the fires we spark with things such as faulty electrical systems are more often started under hotter and drier conditions.

“Human-ignited fires grow more rapidly and release more energy as they’re growing,” UCI Professor James Randerson said in a statement with the study’s release. “They’re more ferocious.”

Brandon Bell/Getty

Passing on the Costs to Customers

“We hear ‘climate change’ and it’s always one of the first things to come out of these utility companies’ response to a wildfire,” Ari Friedman, a partner at the law firm Wisner Baum said. Friedman has specialized in wildfire liability cases for almost 10 years and Wisner Baum is among the law firms suing Southern California Edison over the Eaton fire. Friedman is not a climate-change skeptic—quite the opposite. His point is that the effect of climate change on fires is so well-established that it should not be used as an excuse by utility companies.

“They’ve known about climate change for decades,” he said. “A company can either choose to maximize their profit and their return for their shareholders or spend the extra money to make sure that their infrastructure is safe and robust.”

Wally Skalij/Los Angeles Times/Getty

Friedman said he had thought that the massive liability and bankruptcy PG&E endured after the 2018 Camp fire would provide impetus for greater preventive measures.

“But now we’ve had Palisades, and Eaton, which show we still have a lot of work to do,” he said. “Hopefully this is just another driver to hold these utility companies responsible for maintaining their grids.”

But large liability payments are less likely to spur action if the utility companies can simply pass those costs on to their ratepayers, some critics argue. That’s just what SCE was doing, even as people picked through the ashes of former homes last month.

The utility company asked for, and received, permission from the state’s Public Utilities Commission to have ratepayers pick up the more than $1 billion of liability costs for the 2017 Thomas fire sparked by electrical equipment. State Senator Ben Allen, who represents parts of the Los Angeles area, wrote a letter objecting to the PUC decision.

Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times/Getty

“By allowing SCE to raise rates in order for customers to cover these damages, we are failing to hold them accountable and instead passing their liability onto the residents of the region,” Allen wrote. “It is reprehensible to require these same consumers to assume the financial responsibility for corporate mismanagement and infrastructure deficiencies.” The Thomas fire predated a California law passed in 2019 that created a state fund to help cover the costs of wildfires and capped liability that utility companies face. A spokesperson for SCE said the law requires utility companies to have strong wildfire mitigation plans and to show that they acted in a prudent manner before they can recover costs.

“We have reduced the risk of losses by catastrophic wildfires by 85 to more than 90 percent compared to pre-2018 levels,” Kathleen Dunleavy, SCE spokesperson, said. “That is through the ongoing employment of covered conductors, undergrounding, grid hardening measures, enhanced inspections, expanded vegetation management and the targeted use of public safety power shutoffs.”

AP Photo/Ethan Swope

Questions Still To Be Answered

Colin Weatherby was on the phone with his parents the night the Eaton fire was roaring through the canyon, urging them to leave.

“Luckily, my parents live just east of where the fire started,” he said, which put them upwind of the flames’ path. His parents got out and went to Weatherby’s apartment, where they watched the fire spread and frantically called everyone they knew in the affected area to warn them. Weatherby’s parents’ property survived the fire, but he said many friends lost homes.

Mario Tama/Getty

“Southern California Edison has to answer some questions,” Weatherby said. He wants to know why the company did not power down vulnerable lines sooner, given the forecast and warnings of strong winds. “I think that we should have a clearer picture of what our electric transmission response is to a major storm.”

He is again looking out of his apartment’s aging windows but now at a radically changed view of charred hillsides and burned homes.

“I’ve always joked about how I have the best view in Pasadena,” he said. “Now this view is really just a terrible reminder.”

fairness meter

Click On Meter To Rate This Article